~ 13 min

Textual Account as Evidence

At the end of every day of our journey we journaled and recorded personal experiences. The intent of the journal was to act as a memory device for the events and happenings of the day and to communicate with friends, family and a wider audience of colleagues. Our journaling was recorded live on our WordPress site in order to chronicle our daily activities. The journals lie in the discussion section of our website,(1) each week has a set of journal entries and each journal entry is 200-600 words in length, a dense paragraph. To consider the content of these journals, I coded the content of each journal entry. I read each journal and wrote thematic words that corresponded to the content and literary intent of each paragraph. As I read, certain themes appear again, I read back through the journals a second time in order understand and make connections within the terms throughout the text. This process was repeated until the thematically coded list had reached saturation. This process of thematic coding is often used in Social Science research when attempting to analyze qualitative written or verbal responses. Neil Selwyn’s study of distance learners experience with technology in their education used this technique to analyze the written experiences of subjects.(2)

I practiced this method through the process of coding and recoding thematic elements of the journal texts. I then created a bank of terms that reoccurred most often throughout the text. I then tallied the occurrence of these words to create a list of terms and their frequency. In Figure 15 the most frequent recurring theme that was coded was “history and emotion.” The term “history and emotion” refers to a time in the journal where we wrote about a historical event that took place in the space we inhabited and then reflected on the way that historical happening affected us today. It was a process of connecting with the past in a physical space and time and then recoding that memory and the feeling around that experience in a textual form. The terms “violence” and “history” go hand in hand with the practice of historical reflection outlined in the term “history and emotion”. The term “violence” outlines a time when we were overcome with the presence of historical violence in a part of the landscape, and “history” refers to a time when we take note of a historical event without specific emotional reflection. On day three of our journey we write, “We pass through Sinsinawa Mounds. This high mounded landscape was eventually turned into a convent after being wrestled away from the native tribes that inhabited the area. This was where Chief Blackhawk had his last stand as he was eventually driven across the Mississippi. We cross the Mississippi at the end of the day today.”(3) This reflective moment considers the physical landscape we are experiencing in the present day and attempts to acknowledge the violence that took place in this space and continues to take place in this space when we forget these histories. These occurrences may continue to influence and resonate throughout the environment though we may be unaware of these particular events at any one given moment.

Figure 15

history and emotion 30, weather 25, violence 25, hill or flat 21, river 21, hot or cold 20, landscape 19, history 14, tree 14, worry 12, color 12, water 11, time 8, infrastructure 7, conversation 7, forest 6, rain 5, space 5, elevation 5, plant 5

This practice of reflection is an ongoing theme in our journals and it accompanies a few of the other themes of writing practices. All of our journals have references to the weather: the heat of the day, the cool of the morning, the rain endured, or the wind we fought through. This focus on the weather creates an intensity in the writing when the weather we are facing is specifically harsh. Our day nine journal begins, “Last night’s camp in Mankato saw a severe thunderstorm hit about 2 am. The tents took in water and we had to hold down the poles in the high wind. Everything got soaked so we tried to dry out a bit before we got started.”(16) We do not record the sleeping conditions of every day but this particular night was so significant it was important to record in the text. We do to not regularly record weather information in our journals when the weather we are enjoying is mild and accommodating. Travel journals include weather because weather faced far from home and without known shelter is always concerning. When in a landscape moving through spaces not previously travelled there is a persistent awareness of vulnerability that is intensified by the unpredictability of the weather. This vulnerability is made apparent in the term “worry” that comes up throughout the journals.

On day fifteen, “Farms seem to be 20 miles set back from the road and we have not been in the shade of a tree all day. This is a space we would not want to be caught in a storm.”(5) This worry is not explicitly expressed with the word “worry” but concern is expressed about our safety and about the vulnerability we face while traveling far from personally known paths and spaces. The landscape is the main character throughout our journals. The landscape has color and texture. The landscape has danger in elevation and remoteness. The landscape is the setting of all the themes of our journal. It is the space where we connect with the historical trauma, it is the way we locate time and distance, and it is how we define known and unknown space. In daily travels our local landscapes become invisible because they are such a normalized part of our experience, we do not consider their uniqueness. Once we step outside of our known space and step into a space that we do not normally move, the landscape suddenly becomes a changing character with unknown traits. The journals express the wonder that is possible when experiencing the landscape in a personal direct way. As we move through these landscapes on a bike we experience every foot of the road, every rock, every tree. The speed with which we move through a landscape determines the time we give ourselves to consider the landscape. As we move in spaces that are unfamiliar we often feel a distance from the landscape. This is distinctively different compared to the way we forget the landscape in our daily routine. When we are outside of our own space we stand back and wonder at the whole vista of every landscape. Travelers look at unknown landscapes and try to absorb all of their features. This act is impossible: a traveler can only understand a landscape from a personal viewpoint of outside experience determined by the mode of travel.

On day 33 we reflect about our experiences in Montana: “The landscape and the mountains have so many faces with the changing weather. Sometimes the area looks as though we are in New Mexico and when cloud cover moves in I could swear we were in Alaska.”(18) There are many ways to see or know a landscape, in this case we can only reflect on the landscapes that we travelled through as travelers and academics. We also use other travel memories to compare our experiences with the landscape with this instance of travel. While this textual evidence provides reflective data about the experience of a landscape it is not representative of the landscape as a whole. It is a representation of the landscape as seen as a traveler.

A term that stands out as different from the rest of our thematic words in our journals is the word “conversation”. Our experience was significantly changed every time we encountered another person. Often we met travelers like ourselves marveling at the landscape from an outside point of view, but we also met people who lived in the spaces we moved through who would inform us about local road conditions and local histories. On day twelve: “We even had someone slow down their truck and check up on us and wish us well.”(19) Snippets of these conversations were represented in our journals. We did not record these conversation or copy them down word for word. We often did not even know the names of people with whom we spoke and encountered. The journals record the memories of interactions that construct specific memories of spaces and experiences. These voices recorded in our journals are forever related to the spaces and experiences documented in this journey. Although the interactions may have been transient, the memories of these voices are preserved in our journal accounts and serve as site specific information about the experience of space and place.

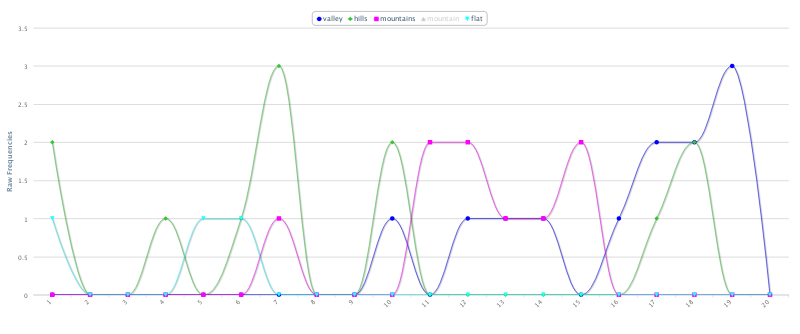

The main recurring themes derived from the terms coded in our journals were “history and emotion,” “weather,” “landscape,” and “conversation”. To double check my own coding of our journals I created a text file of the journals and then used Voyant, a “web-based reading and analysis environment for digital texts”(8) to look at the frequencies of word usage in our text. Access to the text file of our journals is available on Github.(21) Voyant has a built in “Stop Words List” named “English (Taporware)” which disregards the most commonly words used in the English language from the basic counting mechanisms in Voyant. This tool found similar patterns of repeated words in the text which mirrored my own thematic coding process. In Figure 16 a word cloud shows the most frequent words used in our journals emphasizing with size the amount of times the word was used.

Figure 16

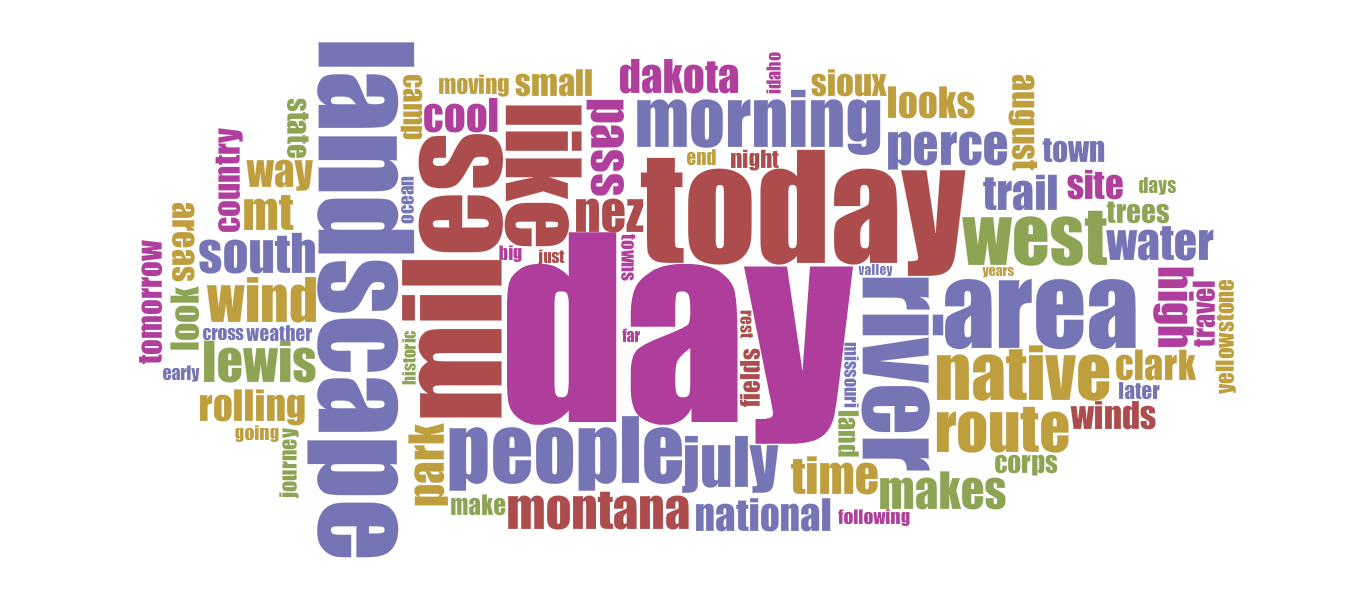

Voyant noted a frequency of the word landscape with 56 mentions. It noted weather words with frequency, wind had 24 mentions. Voyant cannot, however, abstract a theme from textual context. It did not notice the recurring issue of mention of “worry,” or the process of engaging with “history and emotion.” Voyant counted the use of words referring to historical people and Native American tribes. The words Lewis, Clark, Nez Perce, and Sioux were used, but the themes I understood from reading and coding the journals were not necessarily specified. The activity I was recording most acutely was the process of moving through a space and stopping to reflect on the history of the space to try to remember and consider and connect with the historical trauma that took place. Voyant was able to track word frequency that directly mapped our experience of the landscape in Figure 17. Our journal starts with a frequent use of the words “hills” and “valleys” and then makes a transition into the term “flat.” The word “flat” is then superseded by the words “hills” and “valleys” again, only to be replaced by the word “mountains.”

Figure 17

This graph of landscape elevation terms frequency mapped across the text of our journals corresponds to the physical elevation graph represented in Section One, in the mapping of numerical altitude measurements Figure 3. This comparison of a machine reading of our textual evidence and a hand coded thematic reading of our text shows the strength of what is contained in first-hand accounts of textual information as evidence. A journal can capture a complicated experiential emotion that can be read and understood by a reader. The textual work in our project as well as the analytical process in relation to a thematic reading of these texts was inspired by the process of Autoethnography. As defined in the Qualitative Social Research Forum, “Autoethnography is an approach to research writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyze personal experience in order to understand cultural experiences.”(10) This process of reflective writing as a form of qualitative research revealed the experience of communicating with strangers in passing conversations and in-depth discussions. The text of our journal explored the low lying concern and worry over the safety of our exposed condition as travelers.

This process of journaling about a project is an encouraged practice in the Digital Humanities community. In a DH context journaling is a way to reveal the praxis-based research methods involved in the creation of a digital work. For this project the journal text itself was used as a body of data. The original journals in the context are available online at our website (http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/discussion/). The journals exposed our main purpose for initiating this project, to move through the Western United States and consider the historical traumatic events that occurred in the landscape within the 19th and 21st century. This purpose can be obscured when considering only the geospatial data in Section One. The numerical representations of the journey reveal the quantitative experience of hardship as it relates to measured readings of the weather. The textual evidence represented in Section Two complicates the experience portrayed by the geospatial data in Section One. A look at the spatial numerical data collected does not expose the relationship with history that was continually present as we travelled westward through this country. The numerical data informs the text of the journals, allowing the hardships of the physical travel to be measured across a 2,718 mile journey. By engaging with quantitative and qualitative data side-by-side we see how different forms of data tell the story of this journey in very different ways.

Footnotes

- Pollack, Discussion, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/discussion/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Selwyn, Neil. “Digitally distance learning: a study of international distance learners’ (non)use of technology,” Distance Education, 32, no 1 (2011): 85.

- Pollack, Discussion, Week 1, Day 3, June 2, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/out-and-about/week-1/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Pollack, Discussion, Week 2, Day 9, June 28, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/out-and-about/week-2/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Pollack, Discussion, Week 3, Day 15, July 5, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/out-and-about/week-3/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Pollack, Discussion, Week 5, Day 33, July 23, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/out-and-about/week-5/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Pollack, Discussion, Week 2, Day 12, July 2, http://www.crossingthegreatdivide.net/out-and-about/week-2/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- “Voyant”, http://voyant-tools.org/ Web. 6 April 2016.

- Pollack, Github Journals: plain text, http://julia-pollack.github.io/assets/journal/journals.txt Web. 6 April 2016.

- Ellis, Carolyn. “Autoethnography: An Overview,” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12 no 1 (2011)