~ 14 min

Photography as Evidence

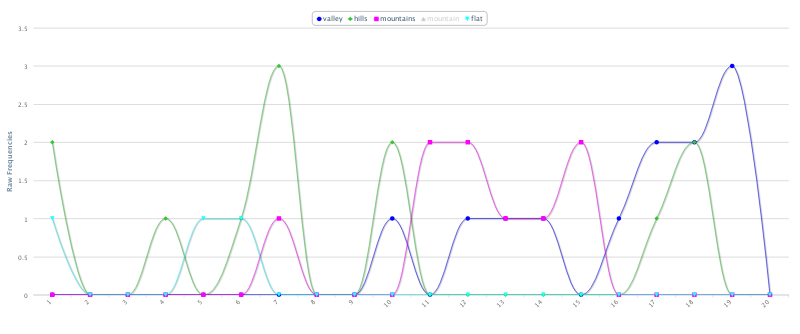

Every day we took photos as we travelled through the landscape. Many of our photos were featured on our website in tandem with our journals; others are not directly being used as a representation of our journey but have been kept for different purposes. All of the photos were taken with iPhone cameras. I have examined every photo and coded each one. I looked at each one and created a list of descriptive words that corresponded with each photo, mirroring this process after the journal coding mentioned in Section Two. After this extensive word list I looked back through the list to create a few main thematic types of photos. I have narrowed my photographic categories down into four main groups: “end-of-day selfies,” “signs,” “sky and ground landscapes,” and “road perspectives.” All of our travelling photos are available online for download and visual analysis.(1)

Figure 18

The “end-of day-selfies” were taken to send back home to family and friends to document and act as proof that I had survived the day. Figure 18 shows an array of “end-of-day selfies.” They act as a kind of personal visual journal. By placing myself in the photo I am adding myself as a framing element in each environment. The end-of-day selfie serves as a direct proof of my presence in the unknown spaces we traveled through. This form of photo is a documentation process that proves accomplishment on a personal scale. By using the convention of the selfie in a travel space, I am playing with an ability to virtually invite the viewer into a space that they are not physically present. The information gained here is personal, noting an accomplishment and taken with the intent to share the photo and allow the viewer access to the space and state of my mind.

Prof Lev Manovich at the CUNY Graduate Center has looked at the impact of the selfie from a global scale, analyzing the large scale patterns found by analyzing selfies from all of the world.(2) This project’s use of photo analysis has done the opposite; as the creator of the selfie, I am conscious of the specific intent and framing of each selfie photo represented. In response to work done in the “Selfiecity project,” Alise Tifentale has looked at the cultural currency of the selfie and explains that, “performing the selfie is at once a private and individual and also a communal and public activity.”(3) The selfie photo is very informative and reveals how a photo is constructed as well as the conditions with which the photographer wishes to be perceived. I attempted to take photos at times in the journey when I was tired or wished to document the end of a long day. They are a way or recording a sense of accomplishment in this sense and act as a kind of humble brag about the enormity of my project of undertaking a cross country bicycle trip.

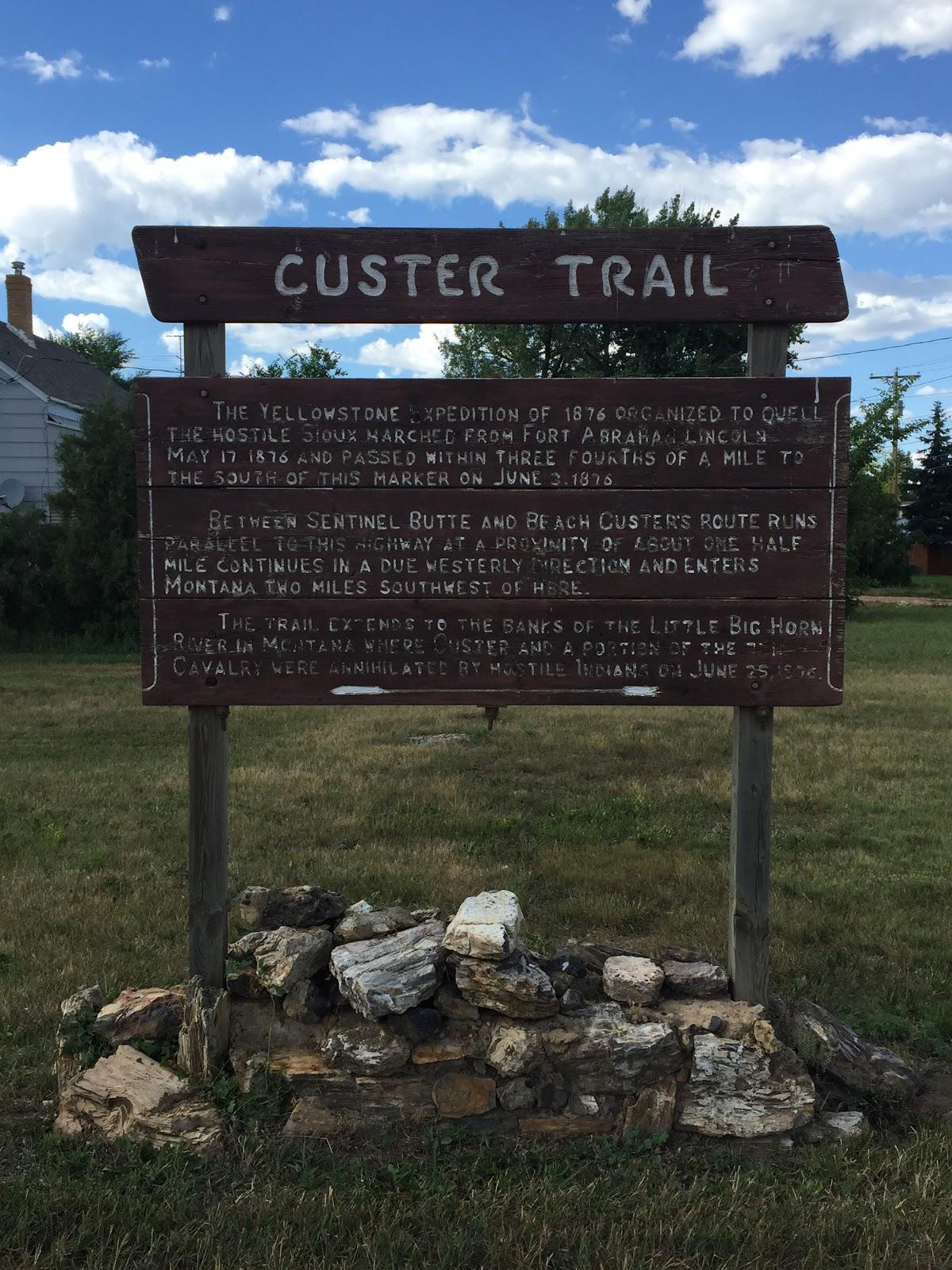

Figure 19

Figure 19 shows an example from the second category of photo we collected. This is a “sign;” the historical sign is a trope of any travel through the American landscape. Informational placards placed on road sides and overlooks populate the American landscape. We encountered signs installed by local groups and signs put up by national park systems. We encountered signs with contemporary notions of space, and signs condemning native tribes for their violent actions against white settlers in the 19th century. We documented and photographed these signs as a way to look at place-memory. How a specific historical memory inscribed on a space with a sign seemed to change radically as we traveled and it was difficult to predict the temperament a group of authors has decided that a sign is needed and that sign is placed in a space for the consumption of whom? Outsiders? Travelers? Each sign has a visual language and is framed by the landscape and its surroundings. The consideration of the importance of signage has been studied in many disciplines; in the piece “Signs in Motion” Keith A. Sculle writes, “They carry specific messages it is true, but they also serve to contextualize or give meaning to their surroundings, both in ways intended and unintended.”(4)

Figure 20

In Figure 20 I have compiled an array of sign photos taken on our journey. The photos themselves serve as a notational device. We photographed them to record the exact language used to inscribe a specific space with history. Each of these photos is a visual record of that information. Figure 19 reads, “The Yellowstone expedition of 1876 organized to quell the hostile Sioux marched from fort Abraham Lincoln May 17 1876 and passed within three fourths of a mile of this marker on June 3rd 1876.” The sign holds the space for many charged ideas about the presence of history in this space as well as Native American relations. The sign is obviously handmade but carefully maintained, there is no mention to the authorship of the sign. The text of the sign assigns its own truthfulness. The sign states that it is three-fourths of a mile from the actual historical happening it describes. The sign’s language also takes a stance about the conflict between native tribes and westward expansion in the United States often reflected in the 19th and 20th centuries. It states that although Custer’s army is weaponized and marching through the landscape the hostility in this space is created solely by the Sioux. This sign was outside of a small town surrounded by a well kept lawn; the presence of this story of history exists for the people that maintain it and serves as a presentation to newcomers. By capturing photos of these signs we not only gathered site specific historical textual information, but we also charted a language for inscribing history on a given space. Not every space is inscribed with signage by people who want to write the historical memory into a space however it is not always clear what determines historic significance though no space is devoid of history.

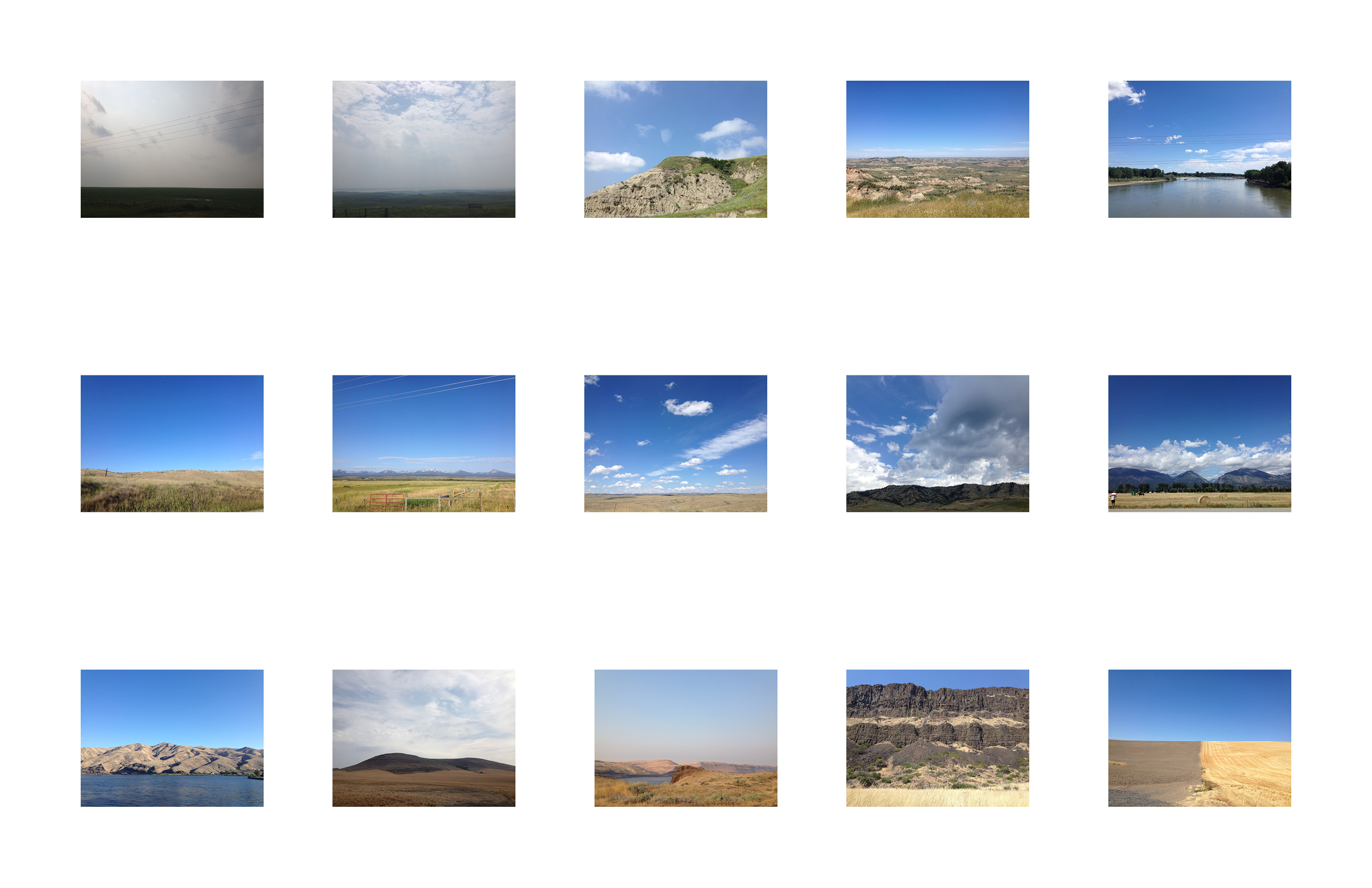

The next category of photo taken was “sky and ground landscapes.” This photo convention reflects a framing of the landscape in the way one might frame a ‘color field’ painting. The “sky and ground landscapes” split the photo into two clear spaces: the land and the sky. They do not have people in them and are often devoid of any kind of presence of human interaction. This is taken in the style of so many great American landscape artists. In the late 1800’s Albert Bierstadt painted the American landscape as an untouched divine landscape ripe for economic expansion.(5) This notion of the American West is captured in the way we take photos of the landscape and mythologize it to this day. In the early 1900’s Ansel Adams followed in Bierstadt’s footsteps creating images of the American landscape that are overwhelming and beautiful and constructed spaces of emptiness.(6) Both of these quintessential American landscape artists from the 19th and 20th centuries respectively created an idealized construction of the American West that taught travelers how to see the landscape in terms of the iconic, scenic vista. This sense of wonder and beauty overcomes a traveler in an unknown space and prompts the traveler to record the experience in a perfectly framed photo, encapsulating a landscape devoid of human presence, although the very presence of the photographer negates this emptiness. By constructing this pristine landscape photo, the traveler is creating a visual narrative that implies that this landscape is being discovered by the viewer for the first time and thus reinforcing the original mythology that created this gaze.

These photos are arguably a representation of a reenactment of the cycle of Western colonization. The idea that the landscape is somehow empty or devoid of life is a false conception of the landscape. This concept, along with the ideals of Manifest Destiny created a moral imperative for western settlers to conceive of the American West as empty and available.(7) The American landscape has been inhabited by peoples long before white European settlers began traveling to the continent in the 1600’s. This construction of emptiness or search for emptiness is a process of trying to reclaim a vision of space and purity in a postmodern landscape. This instinct informs the “sky and ground landscapes.” This photo convention persists in contemporary travel photos and shows a perpetual reenactment of settling in the West. Reanalyzing these photos and realizing that we had practiced this form of documentation has lead me to consider the meaning of these photos. What is understood about their production, and what purpose do they serve for the photographer?

Figure 21

Figure 22

In Figure 22. this array of photos shows the repeated pattern of landscape and sky photo evidence. They all have a constructed viewpoint: they are each empty. In that perceived emptiness there is a sense of abstraction when the images are seen together. The land is below and the sky is above, this split photo creates a kind of abstracted ideal of landscape with this horizon line presenting an impression of infinite space. They serve as a memory-project that places the viewer and the photographer back in the most idealized of spaces. They are potentially harmful photographic evidence if used to describe the landscape, using an abstracted ideal to imply emptiness and infinite space. These representations can potentially be used to practice continued colonization of the landscape.

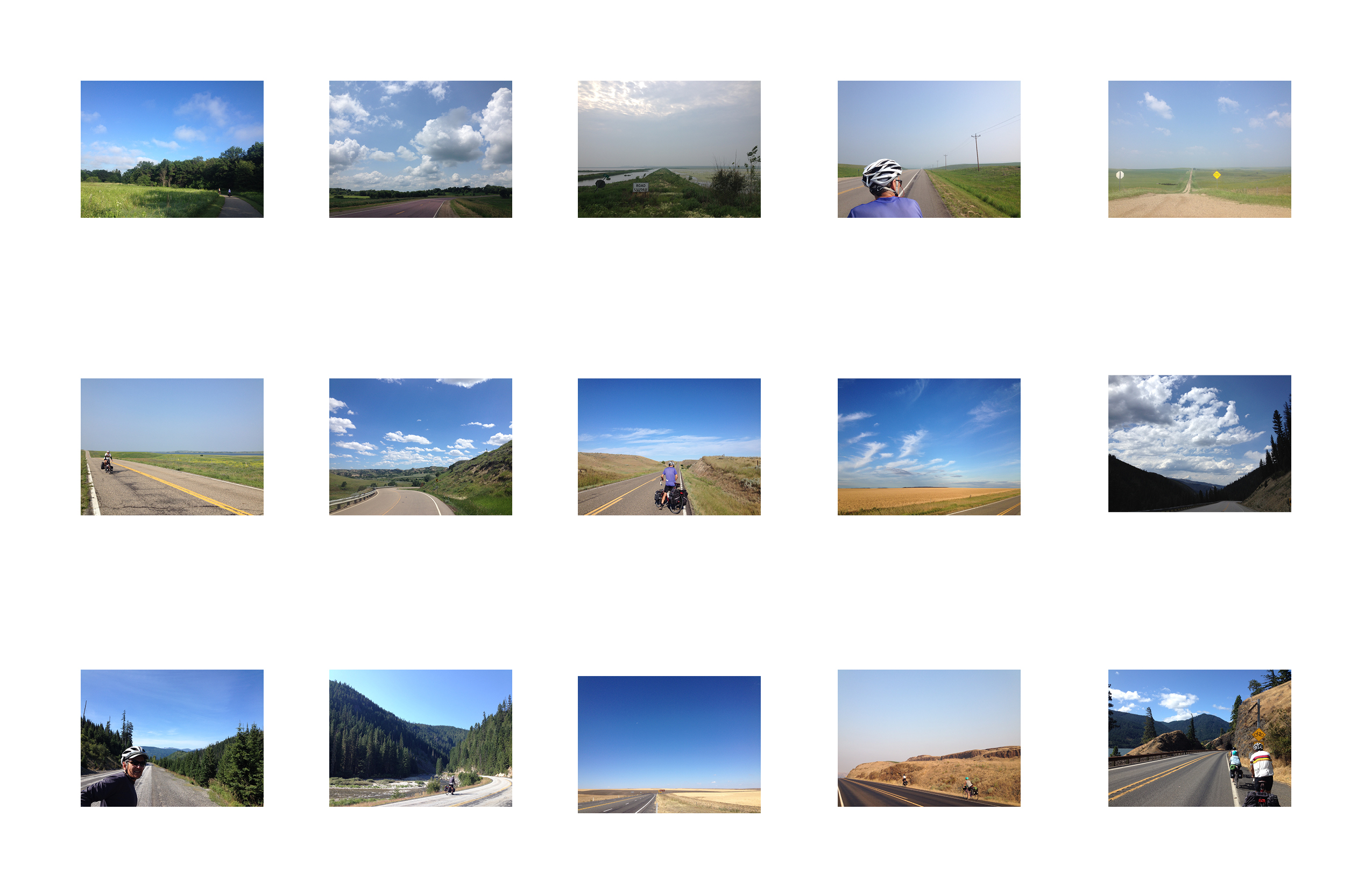

In contrast to the sky and ground landscapes the next photographic type that we identified was the “road perspectives.” This type of photo features the road as a defining character that stretches through the landscape. The road landscapes feature the road as a human made tool that cuts through the landscape, allowing for travel. These images follow some of the same patterns of the “sky and ground landscapes.” They usually carry the same tropes of abstraction and perceived emptiness. As a photographer of the “road perspectives” I would wait until cars and trucks were out of the way before I captured the image. This editorializes the real experience of road travel which is seriously impacted by the presence of cars. The “road perspectives” were taken in areas with little or no traffic. The road in these pictures tracks through the landscape and inscribes itself into the space as if it is a natural element. These road shots inform us about many ways of perceiving the landscape. The quality of the road informs the value and the purpose of the landscape on either side. In these photos the land merely acts a space to pass through and not a location or destination in and of itself. The road divides the natural landscape in order to make it a useful and productive space for economy. Figure 23 shows a “road perspective” whereby the road rolls up and down revealing contour and the elevation, the road is gravel not made for heavy traffic or machinery, there is a far off farm field, and a closer group of grazing cattle. This photo brings another element to the landscape photo in that it gives body to the person who might travel in this road: a farmer or rancher, perhaps. The road could only be used easily by a truck or ATV. The road is constructed so as to suggest that only a few people use this route of travel,– it is a space that is marked off from season to season and constructed perhaps only for private ownership.

Figure 23

Figure 24

The array of “road perspectives” also show a pattern of embodied use. The empty road photos imply use as many of our road photos feature a member of our traveling team as a point of reference. These “road perspectives” with a person give the road details and locates it in time and space. The scope, the length, the smoothness of the road are made apparent when a person with a vehicle is positioned in that space. The road is a penetrating visual element that cuts through the landscape. The road photo complicates the “sky and ground landscape” previously described. While the “sky and ground landscapes” create a perceived pristine land, the road photo drives a human made element through each photo. It does, however, naturalize the idea that a road is the only way to traverse a space. Roads are a major conquering power for traveling technology. Roads allow a traveler to move through a space with the knowledge that the space has been mapped and measured by another who has come before. It provides a kind of traveling communication that is available to those deemed acceptable by the power structures that created the road, it reinforces and suggests its use.

The thematic coding of our photographic evidence gives body to the previous forms of data collected about our travel. The geospatial data and the textual journaling data shed light on measured experiences and thematic emotional experiences. Both the geospatial data and the textual data are using the “landscape” as the topic of discussion. By looking at the photographic evidence as a representation of landscape and experience and only one form of many kinds of data we have about a space we can consider the cultural context of the information collected in the photo. We use photography as a means of recording proof, flawed though it may be, of an experience, but when it is laid side-by-side with many other aspects of truth collection we arrive at a more complete picture of the constructed nature of the photo. A photo of the landscape lends memory to a data point, a description of a conversation is colored by the photo of that space. The creation of history involves a complex process of recording, documenting, and experiencing multiple truths. Many forms of data recording, journaling, and construction are used to construct a narrative. Digital Humanities engages with humanities practices using new digital tools and processes of analysis. This engagement with new tools and new points of view seeks to complicate traditional notions and stratify new notions of history, geography, social science, and statistics to see Humanities scholarship in innovative ways.

Footnotes

- Pollack, Github Journals: photos, https://github.com/julia-pollack/julia-pollack.github.io/tree/master/assets/photo Web. 6 April 2016.

- Manovich, Lev. “Selfiecity.” A DigitalThoughtFacility project, (2014) http://selfiecity.net/#theory Web. 6 April 2016.

- Tifentale, Alise. The Selfie :Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me” (2014) http://d25rsf93iwlmgu.cloudfront.net/downloads/Tifentale_Alise_Selfiecity.pdf Web. 6 April 2016.

- Sculle, Keith A., and Jakle, John A. “Signs in Motion: A Dynamic Agent in Landscape and Place.” Journal of Cultural Geography 25, no. 1 (2008): 57.

- Anderson, Nancy K., Ferber, Linda S, Wright, Helena, Brooklyn Museum, National Gallery of Art, and Bierstadt, Albert. Albert Bierstadt : Art & Enterprise. 1st ed. New York: Hudson Hills Press in Association with the Brooklyn Museum, 1990.

- Spaulding, Jonathan. 1996. “Yosemite and Ansel Adams: Art, Commerce, and Western Tourism”. Pacific Historical Review 65 (4). University of California Press: 615–39. doi:10.2307/3640298.

- Aikin, Roger Cushing. 2000. “Paintings of Manifest Destiny: Mapping the Nation”. American Art 14 (3). [University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum]: 79–89. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/stable/3109364.